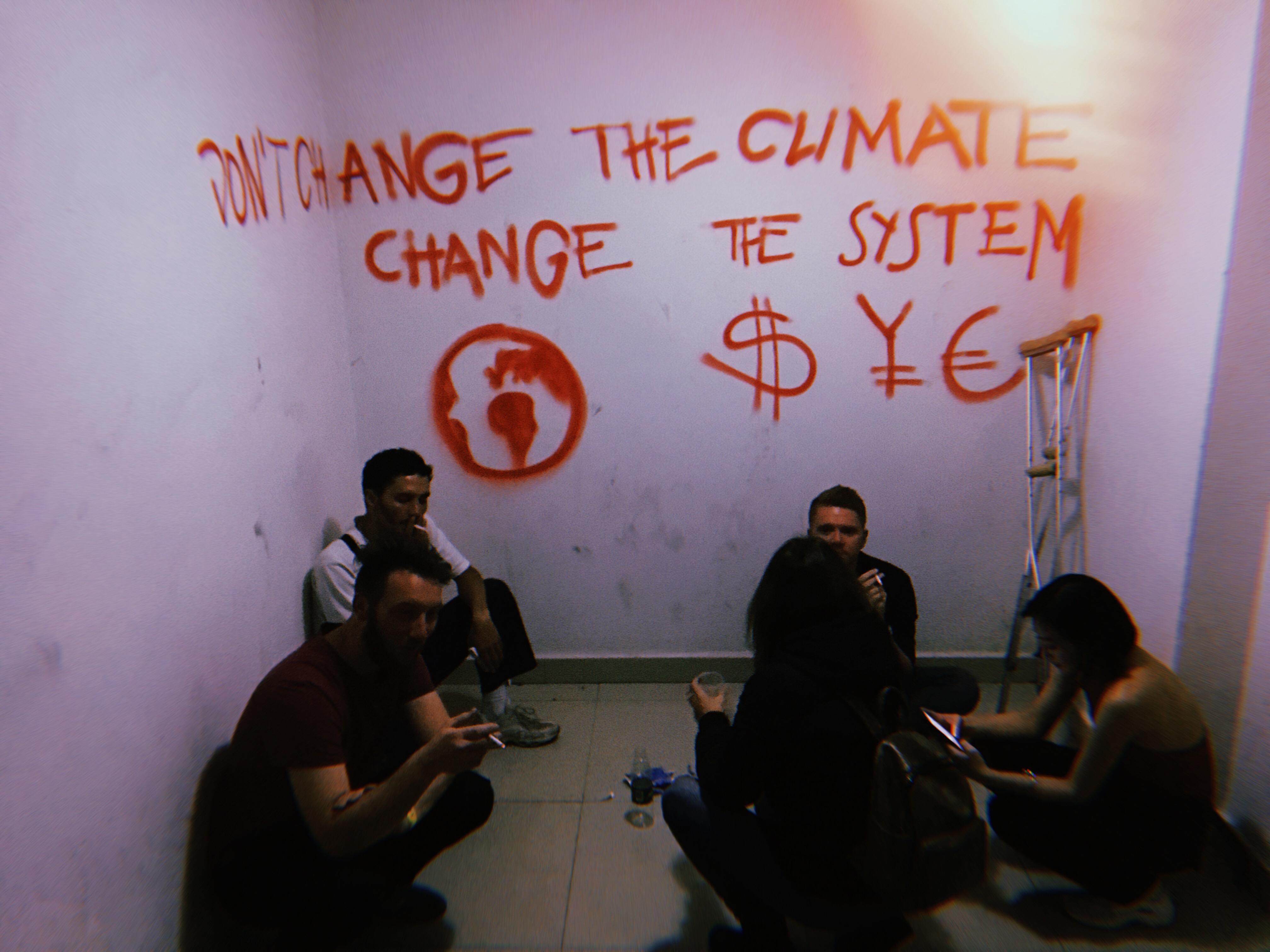

Living amidst the change. Photo by Havoc.

When you live in a place for a long time, you get used to things being the way they are. Change is gradual and often only presents itself from the outside. I realized it when I took my friend Craig to buy a Sim card last year. He had come to visit me in China and wanted to have a Sim card for a few weeks. Not only did he have to provide his passport, but also undergo a full facial scanning process at the counter – open your mouth, tilt your head, blink your eyes, the works. This is compared to 2016, where you could buy a Sim and choose your number from a big paper sheet glued to the newsstand outside Sichuan University, as easy as buying a bottle of water. These days signing up for any social media account requires a phone number and SMS confirmation, which in turn, is connected to your ID or passport. Earlier this year Alipay installed face scanning payment machines across most Hongqi (convenience stores) in Chengdu, which is too next level for me to even comprehend. Moving on.

I realized the change in temperature again when I went to upload Womb’s album Like Splitting the Head from the Body to Netease Music, one of the key music streaming platforms in China. Unlike in 2017, where I simply uploaded the All Seeing Hand’s back catalogue to the site with no questions asked, this year each artist account requires a phone number and ID registration, including a photo of the account holder with their ID next to their face. Furthermore, all lyrics with Chinese translation must be provided for each song. For sure, this is an element of copyright protection here, but moreover a greater sense of monitoring for sensitive content. The silver lining of this of course is that there are Chinese translation of all the beautiful lyrics from Womb’s last album for listeners in China to appreciate.

The list goes on. Last month, Stolen went to perform at RYE Music Festival out of Beijing. They had to perform the exact set list they had submitted and approved. Before getting on stage, the organisers told them to cover all their tattoos. A member of another band was wearing a t-shirt with some kind of message. He was asked to change it or not perform. Next.

Perhaps the most palpable change this year has been regarding performance permits. I never thought this would be enforced in the laidback, chill town of Chengdu – permits were something that existed in Shanghai, where audiences are large enough and gigs make enough in tickets to cover the costs. But again, this has been coming for a while. Around this time last year, key ticketing app Showstart pulled all shows nationwide from the site for two months. When the service returned, only events that had permits could appear on the site, the rest hidden and only accessible with page URLs or QR codes. Whereas Showstart had begun to develop promising connectivity with artist profiles, ticket links and chat forums on the event pages, these latest regulations have been a punishing blow to small local scenes and artists that desperately need to grow audience numbers and ticket sales.

As of March 2019, permits are now technically compulsory for all ticketed live performances in Chengdu, which require artists to submit their ID, lyrics, recordings, setlist and general description of the show content. I use the word technically because there are still shows happening without permits, trying to discreetly fly beneath the radar. But of course, as no one wants to go “have a cup of tea” down at the local police station, many live music venues have been reeling their shows in and avoiding international acts. There is apparently money to be made in taxing the artists. And in Chengdu’s newly regulated market, the costs are astronomical.

This is the play as I understand it: venues without fire and safety certification cannot apply for permits, while venues who have been operating with the correct certification for less than two years must find a middle-man company to manage the process for them. As the regulations have just been only just been enforced, all organisers are needing to outsource the process to such companies, who are currently gouging the market with extortionate, prohibitively expensive prices, with fees for local artists now sitting between 1300 – 2000RMB per gig, and foreign artists at an unspeakable 5000 – 6000RMB. PER. GIG.

Chengdu currently only has two venues with the adequate safety certification – 正火 and NU SPACE. Veteran live music venue Little Bar is preparing to close for several months, ripping out the interior of their largest and newest venue to meet requirements. The city’s smaller venues will wait till the storm rides itself out, quietly ticking over with free entry jam nights and the like. Nothing makes the bar pay QRs ring quite like booze, or Nos balloons.

The effect on live music has been felt with a short, sharp, shock. International bands are cancelling their Chengdu bookings, or leaving Chengdu out of their tour plans completely, much to the disappointment of fans. Local bands who can’t be bothered with the mafan of submitting IDs, set lists and live video, let alone coughing up cash which they are unlikely to make back, are choosing to stay at home. While these are the new rules, the actual enforcement of them is yet to be seen, but the looming threat of checks, complaints or fines hang heavy over the heads of venues and promoters.

With the 2019 calendar dotted with several high profile commemorative political events, the pressure on music, art, film and “culture” looks unlikely to ease up any time soon. However, under such suffocating conditions, steam is being released elsewhere.

Weekend antics at the Poly Centre. Photo by Kiwese

The challenges discussed here are just one side of the coin, one that is ignored or unknown to the vast majority of music punters. In actual fact, parties, gigs and festivals are actually growing in number rather than diminishing and the underground scene continues to thrive in new and innovative ways. It will take time for such a large roll out of rules to fully sink in. In the meantime, many organisers continue to run their events without issue, while bars and clubs are so far unaffected. The demand and support for independent music and culture events is increasing – while the mainstream is still stuck on imitating the hip hop wave, the underground has already moved on. Electronic music and the club scene is thriving, with DJs and beat-based music soaring past the sensors, so far unburdened by permits and content checks required for live bands who fall into the traditional sphere of “punk rock” rebellion and counter culture.

What keeps me in Chengdu amidst all this red tape?

The spirit of change. The pooling together of can-do attitudes. The excitement and activity. The ups and downs. The push and pull. While certainly challenging, it’s never boring. This weekend alone there is a three-day outdoor ambient music festival, an experimental East Asian music collective, the reopening of an underground club with a headline from Ostgut Ton, a return DJ set from respected techno producer Marco Shuttle, not to mention parties of all genres scattered throughout the week, a BBQ at a tattoo studio, a live modular show, and everything in between.

It is non-stop, and a thrill to be part of.

So is Chengdu the frog being unwittingly boiled alive?

Hell no. Chengdu knows the frog is boiling, and has already added the chili, ginger and star anise to cook that shit to spicy perfection.

★

Chengdu hotpot. Photo: The Food Ranger

I have recently written more about Chengdu’s underground music scene over on Radii China:

A Complete Guide to the Chengdu Underground Music Scene

In this piece, I discuss some of the venues, labels and events that are pushing the scene forward, including NU SPACE, .TAG, Steam, Morning and Another Language, as well as some challenges and thoughts for the future.

City Mix: Heady Brew from Chengdu

Here is a mixtape of 21 tracks produced in Chengdu, many of which are unreleased demos, as well as a bit of background on each of the artists.

TRACKLIST

Noise Temple – “Rugga-3” [00:00]

HeLing – “Modular Jam” [04:12]

Stolen 秘密行动 – “Why We Chose to Die in Berlin” [08:17]

Cvalda – “Cemetery Walk” [14:13]

Wu Zhuoling 吴卓玲 – “Glimpse of the Future” [19:23]

Angry Navel 愤怒的肚脐儿 – “K.O. Love” [22:28]

Karmasub – “The Frozen Mountains Icy Skin” [25:37]

FEMME – “Xiaobing” [31:46]

DJ Blue – “Riddle of Sphinx (Original Mix)” [36:38]

Kaishandao – “Hidden Bar (上去)” [42:54]

TY (prod. HARIKIRI) – “那么cool那么swag” (demo) [48:43]

Gaiwaer 街娃儿 – “Untitled” [51:10]

JahWahZoo – “Sunshine” [54:00]

Fayzz – “Walk Man” [57:15]

Sound and Fury – “Coming Down” [1:01:51]

Hiperson 海朋森 – “他像我的老师一样” [1:05:01]

Annaki 安娜其的故事 – “开关” [1:06:37]

Long Travel 浪旅 – “拖延症” [1:11:08]

Deep Water – “Wild Thought” [1:14:15]

Eddie Beatz – “二十一世纪灵魂乐” [1:18:06]

Zhang Ruoshui 张若水 – “回归” [1:19:45]

[…] quicker than the rickety laser printers can spit them out (take for instance this snapshot of what’s happening in Chengdu right now), further widening the gap between DIY spaces forced to stay on their toes and gaudy mid-sized […]

LikeLike

[…] increasing regulations and red tape slowly squeezing the livelihood out of many small music scenes across China, 2019 is […]

LikeLike

[…] in reaction to prohibitive new regulations, mostly as a celebration of underground spaces and attitudes which inhabit them, Subterranea was a […]

LikeLike

[…] exciting drawcard? How and when will the scene revive and under what current conditions, given the already difficult challenges for small venues and increasing restrictions facing live music in China? As clubs in Shanghai reopen and the rest of the country looks to follow, what lies in wait for an […]

LikeLike